Writing for TV: The Leftovers Pilot

- Joseph Morganti

- Oct 3

- 4 min read

The Leftovers, created by Damon Lindelof and Tom Perrotta (based on Perrotta’s novel of the same name), is one of the best pilot’s to examine as a writer. Premiering on HBO in 2014, it offered one of the most ambitious openings of any prestige drama of its era. The first episode doesn’t just set up a world where two percent of the population has suddenly vanished; it announces a series that’s about absence, grief, faith, and the impossibility of closure.

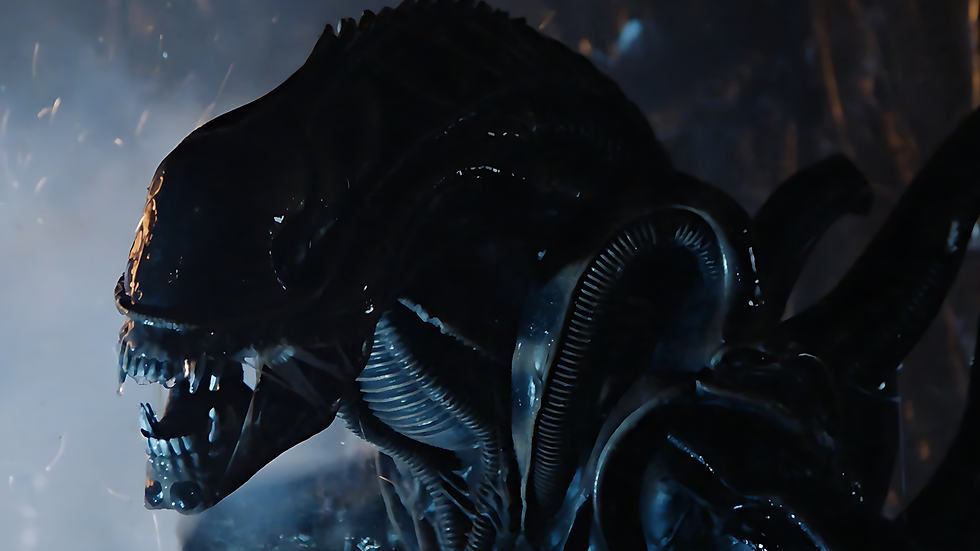

Still from 'The Leftovers'. Photo credit: NowTV

Don’t Follow The Rules

The pilot, directed by Peter Berg, refuses many of the expected rules of television writing which is what I really enjoy about it. There’s no traditional exposition dump. There’s no clear protagonist’s goal presented in the opening minutes. Instead, the episode immerses us in tone and disorientation, trusting that mood can carry an audience until character arcs begin to emerge. Understanding this, the pilot demonstrates how to build a series that’s less about answering a mystery than about sustaining the weight of it.

The cold open encapsulates this. We begin in a laundromat, where a stressed young mother is trying to juggle her crying baby and a phone call. She loses sight of her child for only a second then discovers the car seat empty. Her panic collides with the chaos outside: drivers crashing their cars after their passengers vanish, children calling for missing parents, a world suddenly punctured by the inexplicable.

Without title cards or narration, the show establishes the central event, “the Sudden Departure,” in an immediate, sensory way. A writer studying this choice sees that The Leftovers values emotion over information. Instead of a news montage or an omniscient explanation, we begin in confusion and terror. That disorientation is the point, as it mirrors the experience of the characters who inhabit this world.

Central Characters

Kevin Garvey, the police chief of Mapleton, is the audience’s guide, though he isn’t exactly a conventional lead. You need a great central character in television writing! It can’t be overstated. Played by Justin Theroux, Kevin is frazzled, brittle, and unreliable. The writing presents him not as a heroic anchor but as a man barely hanging on. In the pilot, we see him trying to enforce order in a community that seems increasingly unmoored.

The Garvey family itself, splintered and alienated, becomes a microcosm of a fractured society. Kevin’s son has joined a cult-like group; his daughter is simmering with resentment; his wife has disappeared into a silent religious sect. Instead of uniting in grief, they’ve scattered.

This fragmentation is another core lesson for television writers. Many pilots create cohesion by introducing a “team” or a set of characters drawn together by circumstance. The Leftovers takes the opposite approach: its drama is powered by dispersal. Characters are introduced through their separations, not their alliances. That choice forces the viewer to wonder how these scattered storylines will interact and whether reconciliation is even possible.

Unclear Story Continuation

Don’t forget that television writing should have a balance with the refusal to give answers. For example, the Departure is unexplained, and the pilot makes it clear it will remain unexplained. That decision sparked controversy when the show aired, as many viewers, conditioned by Lindelof’s work on Lost, expected clues to a central mystery.

But the writing deliberately deflects those expectations. By refusing to frame itself as a puzzle-box narrative, The Leftovers positions itself as a story about unresolvable absence. This is crucial for writers to consider: ambiguity can be more potent than resolution, but only if it’s supported by strong character work and emotional truth.

The writing also excels in tone. Dialogue is sparse, naturalistic, and often fragmented. Characters rarely say what they mean; they deflect, they lash out, they go silent. This aligns with the theme of unspeakable loss: language is inadequate, so the show’s most charged moments are often wordless. Kevin’s dream sequences, his silent confrontations with Laurie, or the presence of the Guilty Remnant demonstrate how much can be conveyed through mood rather than exposition.

Theme Importance

Structurally, not much “happens” in terms of narrative advancement. There are parades, scuffles, family dinners, and cult encounters, but no central mission or solved problem. Instead, the episode functions as a meditation on grief and faith. Every character represents a different coping mechanism. Kevin tries to enforce order, even as he doubts his own abilities.

Laurie has abandoned speech altogether. Jill, Kevin’s daughter, flirts with nihilism. Reverend Jamison, introduced in the pilot, clings to a theological certainty that the Departure was not the Rapture but a random event. Their clashes dramatize not plot twists but philosophical collisions. For a writer, this underscores how theme can be the actual driver of drama. If characters are built around thematic conflicts, even a minimal external plot can feel urgent.

It’s also fascinating how Kevin’s dreams blur into reality, creating uncertainty about his perception of reality. Whether it’s how a dead dog suddenly appears on his lawn, then vanishes or a mysterious man encourages him to shoot it.

These touches aren’t explained, but they unsettle the audience, hinting that the line between sanity and delusion is thin in Mapleton. For writers, this is an example of how to integrate ambiguity into character psychology.

It’s also heightened by Max Richter’s score, with its mournful piano motifs, shaping the emotional texture of the episode. For screenwriters, it’s easy to forget that music will later amplify tone, but the pilot is a reminder that rhythm and pacing can be written into the script itself. Long pauses, silent stares, or repeated smoking rituals all invite musical accompaniment that deepens the atmosphere.

Elliptical, Not Linear

Looking at the craft, the pilot’s structure is elliptical rather than linear. It doesn’t build toward a single climax but accumulates tension through juxtaposition: Kevin’s unraveling psyche, the parade fight, the Guilty Remnant’s silent march. The episode ends without resolution, only escalation.

This is risky in a pilot, since audiences often expect a payoff, but it works because the tension is thematic, not plot-driven. The question isn’t “what happens next?” but “how will these people endure?” Writers can learn from this that a pilot doesn’t need to wrap itself neatly–it needs to generate a durable set of questions and conflicts.

Lastly, I love when writing is both exemplary and unconventional. It demonstrates that you can write a pilot that defies formula if you replace conventional narrative hooks with emotional intensity, thematic coherence, and atmospheric immersion.